Sergei Eisenstein

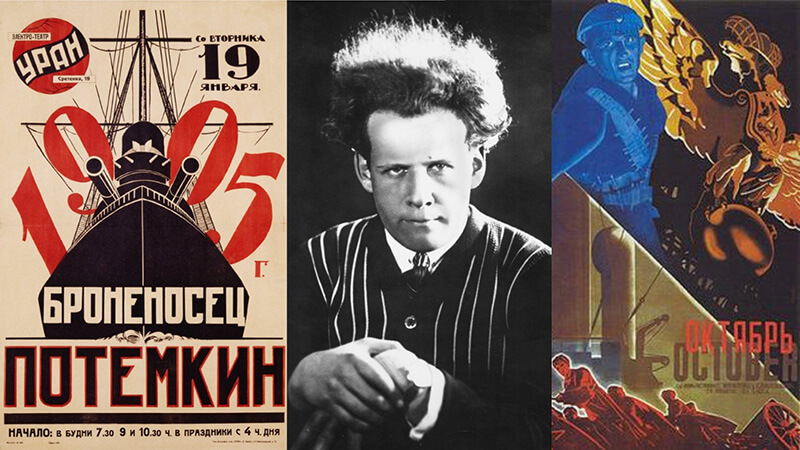

After 1890, film-making experiments gained momentum around the world. Although film production in Soviet Russia began sparsely as early as 1898, the process gained real momentum after about 10 years. During this period, Russia was on the threshold of an unprecedented revolution. The Russian Revolution and the First World War caused a great upheaval in all spheres of folklore. Surprisingly, even in all this fanfare, the film had influenced diplomats and philosophers like Lenin. He was of the opinion that ‘cinema’ is a very important art medium. So after the revolution, he really helped the film business. Around this time, Russian cinema had two ingenious directors, Kulasev and Vartav. But Sergei Eisenstein has to be named as the director who really brought the fame of Russian cinema to the world.

Sergei Eisenstein was born on January 23, 1898. During the Russian Revolution, he worked for some time as an engineer in the Red Army. He came to Moscow in 1920. There he began working as a set designer in the experimental theater. There was always something different in his head than the usual chakori. He once came up with the idea of presenting the boxing scene in a play to the audience. But the director rejected it. He later performed a play called ‘Gas Mask’ directly at the Mask Factory. But the audience did not digest such ‘reality’. That experiment fell apart.

He took his first lessons in this art at the Kulshev Film Training School in Moscow. But even here, his thoughts were moving in a different direction than his predecessor. He was of the opinion that there should be a systematic study and scientific meeting behind every concept. He thought about how film could be developed independently of the medium of drama and developed an effective technique called ‘montage’.

In 1924, he got his first chance to direct with the film ‘Strike’. He used the technique of ‘Intercutting’ effectively in this film. On one occasion, after showing a scene of a police report, he immediately showed a close-up of an owl. In the same way, while showing that soldiers are killing innocent civilians, he also showed the slaughter of animals in the slaughterhouse. He was the first to make such symbolic use of film language.

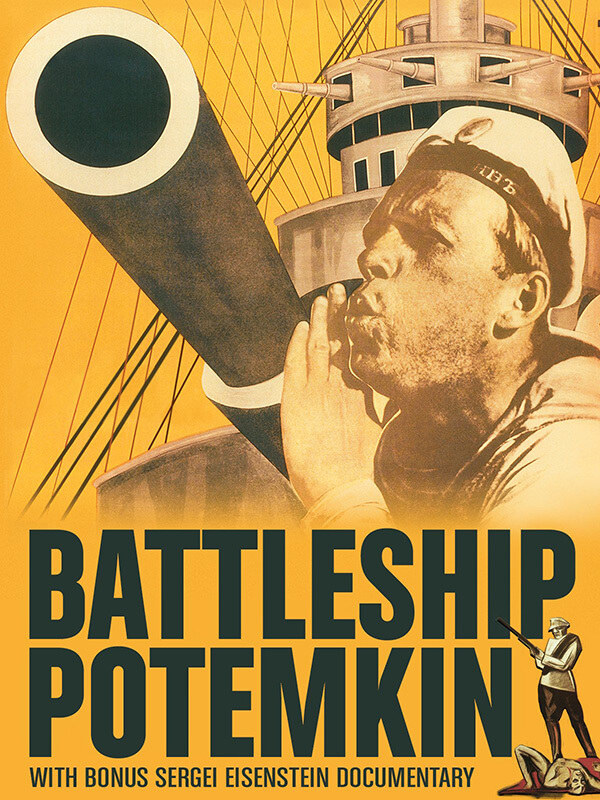

In 1925, Eisenstein released his second film, Battleship Potemkin. This is from the world of cinema

Considered one of the greatest films of all time. In this movie, he has told a story about the revolution. He portrayed the sailors’ revolt against the Tsarist regime in 1905. Rotten meat is given to the sailors on board the warship Potemkin. They refuse to eat this food, but are subjected to disciplinary action. At such times a sailor named Vakulinchuk appeals to the workers to be fearless by uniting.

The film features a series of unforgettable scenes. Eisenstein did not want to tell just one incident. He wanted to convey to the audience what he felt. In this 70-minute film, he created a number of thrilling scenes, weaving a web of human emotions around it. On one occasion, the captain threw tarpaulins on some of the sailors and made them stand in front of a group of soldiers and ordered them to shoot at them. At the same time, Vakulinchuk makes a dramatic appeal, “Brothers, who are you shooting at? We are your brothers. “The soldiers refused to shoot. The sailors revolted. But in this fight, Vakulinchuk is killed.

The boat arrives at Odessa Harbor. Vakulinchuk’s corpse is placed on the dhakka. As the news spread through the city, thousands of people rushed to the port. The sailors are spontaneously welcomed. But the rulers do not consume it. A detachment of soldiers suddenly starts firing on these innocent civilians. Many fall victim to gunshot wounds. In response, guns fired from boats set fire to city palaces.

The boat passes through the harbor and is again surrounded by Tsar’s troops. The boat makes the same emotional appeal as before. Soldiers refuse to open fire on the boat. The boat moves forward safely. The depiction of indiscriminate firing by soldiers on innocent civilians in this film has been hailed as one of the most memorable scenes in world film history. While I was doing an appreciation course at the Film Institute, we were shown this episode of just six minutes in cinema. Watching this event was an unforgettable experience. Next I watched the whole movie.

This event, known as ‘Odyssey Steps’, has been seen many times in the history of cinema. The mind still trembles at the sight. (The film is now available for viewing on the Internet.) When the scene begins, citizens happily gather to greet the sailors. A close-up of their smiling faces, moving hands, suddenly reveals a line of soldiers’ shoes descending disciplined from the steps. The background music changes now. Just an ominous suggestion. People run to Saravaira to see the soldiers. Now a log shot is used to show the magnitude of those steps. Because of that background, people become short and weak. Someone falls while running. Someone gets up. A boy is running lamely with a sigh of relief. The disciplined conduct of the soldiers shows that their humanity is over and they have only become a machine. Gunfire erupts. People are terrified. A close-up of a man’s frightened face comes to the fore. Then only his widened eyes cover the curtain. It is as if fear has now increased. The intensity is increased. Shots of soldiers and civilians are shown alternately. A woman picks up an injured child and starts climbing the stairs. Neighboring corpses began to fall. She cries apologetically. ‘My son is sick. Don’t shoot him … ‘But no one can pay attention to her. The chase of citizens continues. Another woman would have carried her baby in her car. She is shot by soldiers. Her pain-stricken face appears on the screen. As it collapses, it hits Babagadi. Babagadi starts descending rapidly from the high steps. Now, the speed of the scene has increased, shots of Alton platoon soldiers, fleeing civilians and the wheels of the falling wagon can be seen on the screen. The speed of the background music is increased. In between, a close-up of a child sleeping in a car is seen. Now the tension in the minds of the audience is also increased. We are worried about whether the little one will be shot or not. Manoman wishes not to take the pill. That child would now have become a symbol of innocent helpless mankind.

Just realizing how much effort Eisenstein must have put into filming this six-minute scene is evident as he watches the episode once again. (At first glance, we are engrossed in that emotion.) For effective use of photography and compilation, this scene is taught and studied in film institutes around the world.

Battleship Potemkin is the first film starring a common man. That is why it was also called the epic of the community. Eisenstein later became known as an “artist who expresses the language of the camera.” This movie had a great impact not only on the students but also on the general audience.

There is controversy as to whether the Odyssey Steps incident is true or not. Many believe that it should be imaginary.

(The end of the film, however, is fictional. In fact, the sailors’ revolt was brutally crushed.) Roger Ebert, a well-known cinematographer, writes:

The director has portrayed her so effectively that it is great that people have come to understand her truth. ‘ Eisenstein effectively used the technique of ‘intellectual montage’ in this film. He was also a great writer.

His prolific writing on the language of the film is available in six volumes. His bestselling books are The Film Form and The Film Scene. Although the movie ‘Battleship Potemkin’ was famous all over the world, it was banned in England for many years. The British feared that the film would provoke the workers.

But the career of such a great director turned out to be very tough. Pure art was of no value in the atmosphere in which the winds of communism were blowing in Russia. Eisenstein’s October (1927) was criticized by the Communist Party. He could not get any more films for directing. A few days later, an American company invited him to the United States to produce a film. There he wrote the scripts for some of the films. However, his artistic approach and the business approach of American companies could not be reconciled. An example in this regard is very eloquent. David Selzenik was then M.G.M. Was working for. He had seen ‘Battleship Potemkin’ and exclaimed, ‘Cinematographers should study Raphael in the same way that painters should study Raphael.’ Eisenstein wrote the screenplay for MGM’s American Tragedy. “The most moving script I have ever read,” Selzenik said of the script.

Surprisingly, it was Selzenik who advised MGM to reject the script. Because, the film on this screenplay will be very expensive and more importantly, the happy American audience will have to experience two hours of sadness after watching this film. Although artistic cinema was not classified as ‘commercial cinema’ at that time, the gap between the two began to widen.

Eisenstein returned to Russia in 1930 after failing. Renowned author Opton Sinclair was a fan of Eisenstein. He invited Eisenstein to Mexico and gave him a project to make a film.

Sinclair also invested heavily in it. But here, too, American history repeats itself. He returned to Russia. However, as he moved to the United States and Mexico, Russian communists began to view him with suspicion

His mental balance also deteriorated somewhat. This extraordinary intelligent and sensitive artist could not bear this neglect, this failure. He had to be kept in a psychiatric hospital for some time. Shortly after his recovery, he worked as a teacher in a film school. He later got some films. Among them, ‘Evan the Terrible’ was his predecessor. He received the Stalin Award. However, the next part of the film ‘Evan the Terrible-Part 2’ was again disliked by the government. Some of its reels were confiscated and burnt.

Eisenstein died in 1948 at the age of 50 from a brain hemorrhage. On the occasion of his birth centenary, two coins of two rubles were minted in Russia on January 23, 1998. The coins bear the image of Eisenstein. This is the usual story of the artist’s fate, neglect and posthumous honor, isn’t it?

Vijay Padalkar